Introduction

Over 25 years ago, the U.S. Department of Education and the National Endowment for the Arts partnered with the National Assembly of State Arts Agencies and Council of Chief State School Officers to create the Arts Education Partnership (AEP) to ensure that all students have equitable access to an excellent arts education.

From the beginning, we believed that a well-rounded education includes the arts as a core academic subject, providing students with experiences that build their critical thinking and problem-solving skills, enhance their social emotional development and improve academic achievement. Through its work over the last quarter of a century, AEP has coalesced a network of more than 100 organizations to become the nation’s hub for arts education research, policy and practice.

Through AEP, we have engaged thousands of arts partners, professionals and educators to discuss important challenges about arts in education, and we have created groundbreaking publications, studies and online tools that are used to inform strategies and evidence-based practices both for distinct arts instruction and for integrating arts into the curriculum and students’ learning experiences.

We celebrate a $17 million joint federal investment in AEP over 25 years. We also celebrate 25 years of a successful partnership by acknowledging the many federal leaders and arts professionals, researchers, foundation leaders, educators and AEP staff members who led the work, and those who continue to lead the work of AEP. We appreciate the level of professionalism and expanded capacity our cooperator, Education Commission of the States, brings to the management of AEP.

Through celebrating 25 years, we take the opportunity to recognize what has worked and is working well and why, but we also have an opportunity to look forward to the future of possibilities. AEP has survived and thrived over the last 25 years, and the nation is now faced with historic challenges. Arts education can and will play a critical role in healing the nation, and AEP will continue to coalesce its partners and affiliates to address the new challenges and important issues that have come to the fore through research, reporting, counseling and convening.

Our work is only beginning. There is so much more to be done to ensure all children have an opportunity to participate in the arts. We will chart and pave a path forward – together.

Ayanna Hudson

Arts Education Director, National Endowment for the Arts

Nancy Daugherty

Arts Education Specialist, National Endowment for the Arts

Sylvia Lyles

Director, Office of Well-Rounded Education Programs, U.S. Department of Education

Bonnie Carter

Group Leader, Arts in Education and Literacy Programs, U.S. Department of Education

A Message from AEP Director

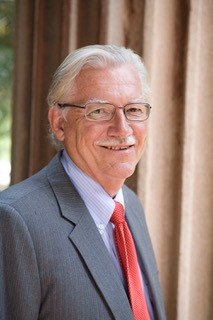

Jamie Kasper

About ten years ago, I was standing in the lobby of a hotel in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, grabbing a cup of tea while attending a statewide arts education event. I have a clear memory of Clyde McGeary — a visual artist and educator who was in his late 70s at the time — saying to me, “We have to capture the firsthand modern history of arts education before those who lived it are gone.”

Fast forward to 2019, and I stepped into the role as director of the Arts Education Partnership (AEP). Almost immediately, Dick Deasy, the first AEP director, reached out to share that there was a group of retired arts education leaders interested in capturing the early work of AEP and policy decisions that led to its founding to commemorate the organization’s 25th year. With Clyde’s voice still in my head, I moved forward working with Dick and the other authors who wrote the first three parts of this history.

Here’s the issue that became apparent to me as we worked on those parts: The policy decisions and early work of AEP were made and done by groups of people who do not represent the rich diversity of America. As of the writing of this document, we’re in August 2020. A combination of the global SARS CoV-2 epidemic that has disproportionately impacted Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) compared to other populations and uprisings protesting long-standing oppression of and violence against Black people have focused public attention on racism and systemic inequalities. I am feeling tension between wanting to capture memories from the people who lived them while also recognizing that they represent one track of history as remembered by one homogeneous group of people.

With that recognition, the authors offer this document not as THE definitive history of modern arts education, but as a starting point for conversations about how events, policies and people that influenced the formation of AEP in 1995 fit into the larger context of arts education. The authors recognize that AEP’s — and AEP partners’ — work was not the only arts education work happening during this time and that important work occurred in BIPOC-led, rural, grassroots and other organizations simultaneously. In 2020, AEP staff members are working to build authentic, lasting relationships with these organizations and look forward to collaborations in the future that ensure their work is integral to AEP.

Jamie Kasper

Director, Arts Education Partnership